Weather Balloons

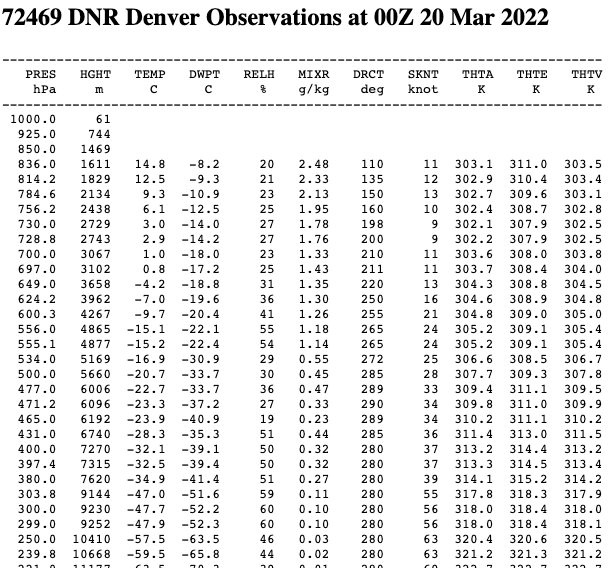

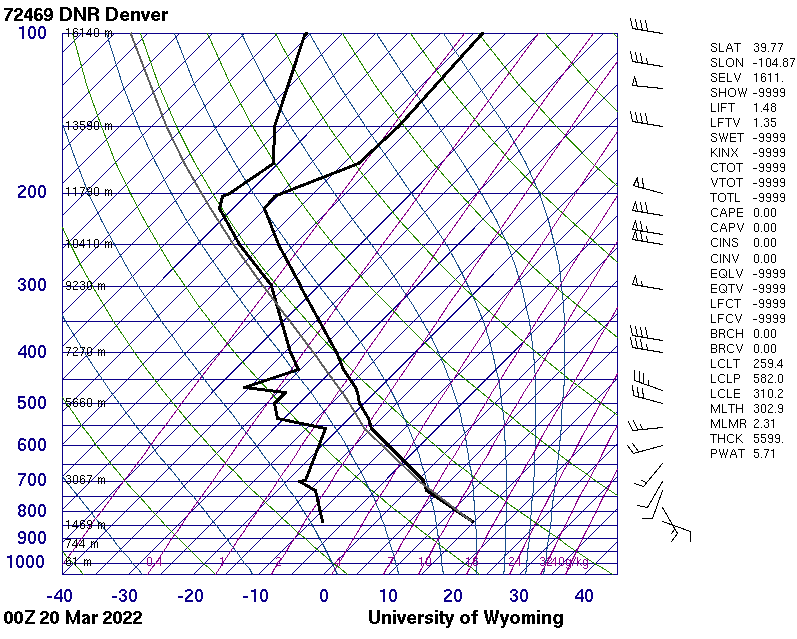

Weather balloons give us our best look at the vertical structure of the atmosphere…with limitations.

Weather balloons are an important component when it comes to gathering data about the vertical structure of the atmosphere. They give meteorologists a profile from which they and the computer weather models can make assumptions about the atmosphere and the weather it may produce in the short term. Weather balloon soundings began in the late 1930s and have been in continuous use since.

Weather balloon soundings are taken twice a day from 92 stations; 69 in the conterminous United States, 13 in Alaska, 9 in the Pacific, and 1 in Puerto Rico. NWS also supports the operation of 10 other stations in the Caribbean. Lasting about two hours, the balloon’s flight can cover over 125 miles and an altitude of as much as 100,000 feet. As you can imagine, the balloon and its radiosonde instrument package must endure winds of up to 200 miles per hour, temperatures as low as -95° C, relative humidities ranging from 0 to 100 percent, and air pressures as low as few thousandths of that found at the earth’s surface.

Limitations

The weather balloon program does have some limitations, however. In many states there are only one or two NWS Weather Forecast Offices with launch capability. In my home state of Colorado there are two, Denver and Grand Junction. California, not surprisingly, is bracketed by six stations, although two are in western Nevada and one in southern Oregon. The result is large areas of the US that have no sounding data. The computer models have to interpolate soundings for the remainder of the country from the available observations.

Another disadvantage is that the vertical sample of the atmosphere taken by the balloon’s data sensors, or radiosonde, is not exactly vertical. The balloon drifts horizontally with the wind as it rises, so the profile is more of a slant aligned downwind of the launch station. Nevertheless, the sounding data gathered by the instrument pack is crucial to providing meteorologists with a snapshot of the atmosphere.

Components

The Balloon

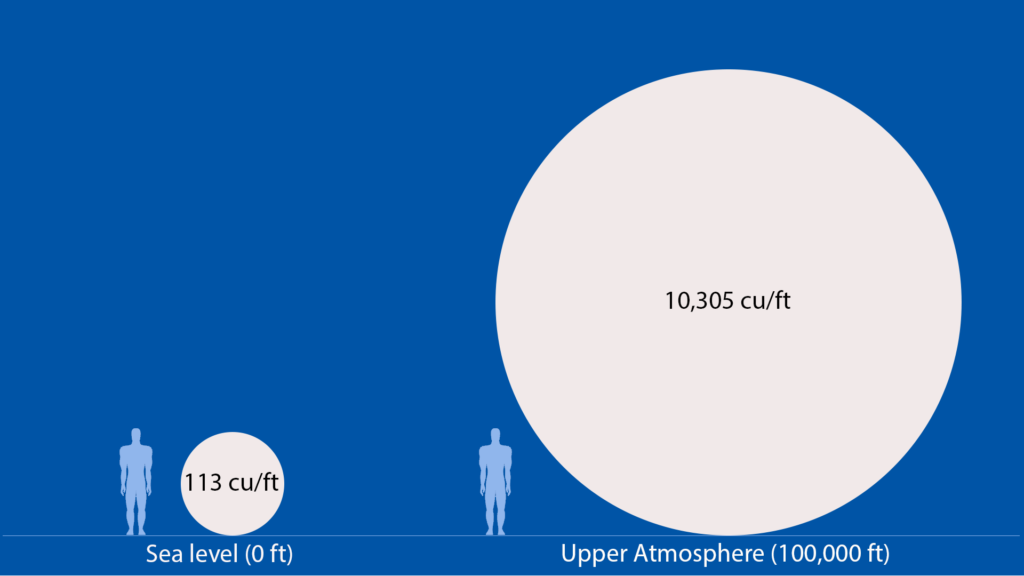

The weather balloon itself is made of synthetic neoprene rubber about 0.051 mm thick at launch, stretching to 0.0025 mm at bursting altitude. The balloon is filled with hydrogen or helium and is approximately six feet in diameter at launch, stretching to almost 20 feet in diameter at the apex of its flight.

The Radiosonde

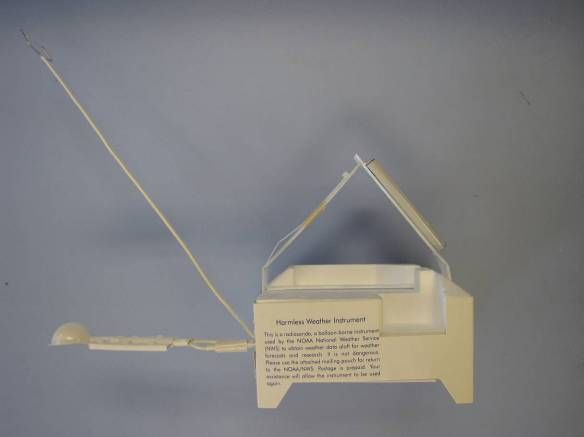

The radiosonde is the instrument package that takes the atmospheric readings and transmits the data back to listening stations on the ground. It is powered by a small battery pack. The package weighs about four ounces, down from almost two pounds several years ago. There are several manufacturers and models of radiosondes available. Currently, the NWS uses two models, the LMS-6 built by Lockheed Martin and coupled to an LMG6-R ground receiver, and the RS92-NGP built by Vaisala. Newer radiosondes are factory calibrated and do not require baseline calibration before a flight.

The radiosonde measures temperature, relative humidity, air pressure, and GPS position and relays the information to ground stations every one to two seconds using a transmitter of approximately 300 milliwatts. The transmitter operates on frequencies from 1676-1882 MHz or around 403 MHz. Additionally, wind direction can be determined by tracking the balloon’s position throughout the flight. A radiosonde that measures winds aloft is called a rawinsonde.

To aid in the recovery of the radiosonde after the balloon bursts, a small parachute is attached to the package and slows the radiosonde’s descent back to earth at a speed of about 22 miles per hour. Attached to the radiosonde is a mailing bag and instructions on how to return the package to the NWS, where it will be refurbished, tested, and deployed on another flight, saving money. Of approximately 75,000 balloon launches each year, about 20% are recovered and returned.

The Flight Sequence

About two hours before launch, the balloon is filled with hydrogen or helium, enough to lift a payload of 1,200 to 1,600 grams. Then the radiosonde is attached to the balloon with 75 feet of string. A parachute is also attached between the balloon and the radiosonde package.

Just before launch, the NWS will coordinate with the local FAA air traffic control center for clearance to launch the balloon.

Once the balloon is launched it will begin its climb into the atmosphere, relaying its data to the ground station. As it rises the air pressure outside the balloon decreases, so the balloon begins to expand. At some point during the flight, the elastic limit of the balloon will be reached and the balloon will burst. The parachute will lower the entire assembly to the ground.

For NWS operational purposes a weather balloon flight that does not reach at least the 400 hPA level, or approximately 23,000 feet, or suffers the loss of data for six minutes or more is considered a failure and may necessitate a second launch.

What If I Find a Radiosonde?

As mentioned, approximately 20 percent of radiosondes are found and recovered by citizens throughout the coverage area. The radiosondes are perfectly safe to handle and most have attached a post-paid return envelope with instructions on how to mail the radiosonde package back to the National Weather Service. Additional information can be found here.

Automated Launchers are Coming

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, parent of the National Weather Service, in 2016 began testing in Alaska technology to automate launches of weather balloons. Launch stations in Alaska suffer from some brutal weather conditions and are spread over large distances. Recruitment and retention of personnel to do the balloon launches is a perennial problem. Whereas a typical balloon flight can take as much as four hours of staff time each day from preparation to the conclusion, an automated launcher requires only about one hour of service every twelve days, along with some routine calibration and maintenance. The program has proven successful and expansion to most of the Alaskan stations is in progress. Further expansion into the lower 48 states is also likely.

Weather balloons have long been a staple of meteorological atmospheric sampling. Not only launched by the NWS, balloons are also launched by military installations and ships at sea. All of this data, including that from many international stations, are shared through cooperative intergovernmental agreements. Observations from over 800 upper-air stations worldwide provide critical profiles of the atmosphere’s structure and remain an important component of our daily forecasts.