Imagine, if you will…

In the 1990's a voice actor named Don LaFontaine provided voiceovers for hundreds of movie trailers. LaFontaine would begin his voiceover with a baritone voice saying "In a world where…,” which has become an icon. In honor of LaFontaine, who passed away in 2008, we'll begin this article with…

In a world where the planet is:

- tidally locked,

- is the exact same size as the Earth,

- the axis is not tilted,

- the surface is perfectly smooth, no mountains, no plants, no oceans,

- like the moon, the same side faces the sun at all times,

- the planet's color is a neutral gray, absorbing and reflecting the sun's rays evenly,

- and, the atmosphere is identical to Earth's.

What does its weather look like? First, to distinguish between the real Earth and our fictional one, let's call our new planet Barsoom, after Edgar Rice Burroughs' fictional Mars.

On our Earth, the air seems to circulate constantly and chaotically, but what would the circulation look like on Barsoom?

The biggest factor in this planet's circulation is the fact that it is tidally locked. Take our moon, for example. The moon always shows the same face towards Earth. Anytime we're looking at the moon we're seeing the same craters, mountains, and mares ("oceans") each time. How does this happen?

The moon takes 27.3 days to orbit around the Earth. The moon also takes 27.3 days to rotate about its axis. Because the moon's axial rotation matches its orbital period, we never see the backside of the moon.

For Barsoom to be tidally locked, the planet's axial rotation would be 365.25 days, matching its orbital period around the sun of 365.25 days.

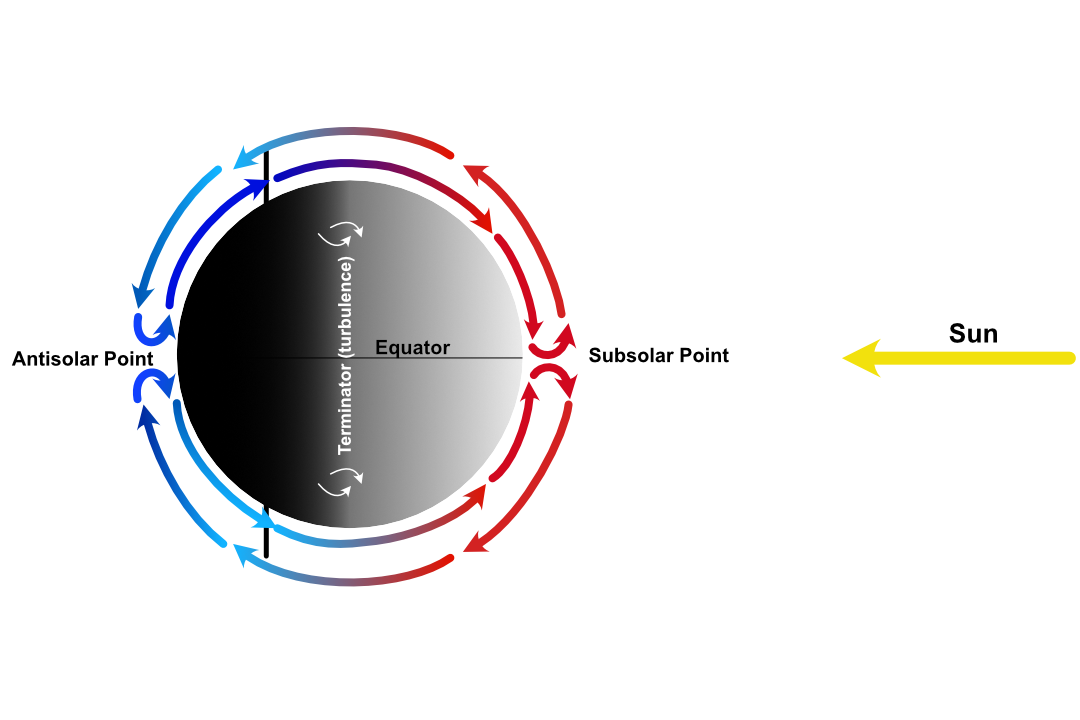

The point where the sun's rays strike the planet perpendicularly would be the hottest spot on the planet, the subsolar point. With no axial tilt, the subsolar point sits at the equator, dead center on the planet's sun-facing disk. On the night side, the point directly opposite the subsolar point, called the antisolar point, would also reside at the equator.

What does this mean for Barsoom's atmospheric circulation? Like the moon, the side with permanent sunlight would, of course, be extremely hot, with the hottest temperature at the subsolar point. The dark side, with permanent night, would be extremely cold, with the coldest temperature at the antisolar point. With no axial tilt, heating and cooling would be symmetrical across both hemispheres.

Hot air rises, and so it would in this scenario, with the less dense air at the subsolar point rising into the upper atmosphere. From there, the air would flow outward in all directions from the subsolar point, with the strongest flow toward the nightside across the terminator, and weaker flow spreading poleward on both the day and night sides. This creates a giant area of low pressure on the planet's daylight side.

The opposite would happen on the night side. Cold, dense air would be drawn across the surface towards the daylight side in an attempt to balance the low pressure caused by the rising air, creating a giant area of high pressure at the antisolar point. Air above the antisolar point would sink, or subside, creating high pressure at the surface.

What we end up with is hot, less dense air on the day side rising into the upper atmosphere, and flowing toward the night side, cooling, and sinking toward the antisolar point, as cold dense air from the antisolar point flows along the surface toward the subsolar point, where it is heated and rises again, completing the cycle.

Things get interesting at the terminator, the line separating day from night. Here, the sharply contrasting temperatures would result in extreme winds and turbulence as the hot and cold air masses clash, mix, and turn over. For life as we know it, this would likely be the only narrow region on the planet where temperatures might be moderate enough to be comfortable, if you could find something to hold onto.

Axial Tilt

Earth's axis is tilted 23.5°. How would that affect Barsoom's circulation?

Let's assume the planet's axis is tilted 23.5° directly away from the sun. This would move the subsolar point from the equator to a point 23.5° south. On the night side, the antisolar point would move from the equator to a position 23.5° north. This presents a whole new level of complexity for Barsoom.

With the subsolar point now south of the equator, the southern hemisphere is noticeably warmer than the northern hemisphere. On the night side, the antisolar point's position north of the equator means the dark side's northern hemisphere is colder than its southern.

Because of the tilt, the subsolar and antisolar points are closer to the poles, and the formerly symmetrical flow between hemispheres would now be asymmetrical, with meridional flows towards the poles becoming stronger.

Were the axis to be tilted directly toward the sun, the subsolar and antisolar points would each shift to the other hemisphere and the circulation would also shift accordingly. If Barsoom's axis were perpendicular to its orbital plane (no tilt relative to the sun), the tilt's effect would be zilch.

Wrapping Up

The atmospheric circulation on our fictional Barsoom, with or without axial tilt, is somewhat more complex than presented here, but the general idea is that the air movement on Barsoom is essentially a giant Hadley Cell, with less dense hot air rising and flowing toward colder regions, while cold, dense air flows from the cold regions to the warmer regions.

Our Earth, of course, rotates, and that introduces many more complexities to our circulation: Hadley Cells, Ferrel Cells, Polar cells, Rossby Waves, and Coriolis force. We'll explore these systems in our next article in this series.